What is Double Tracking

Introduction

Ever since the rise of pop music, producers have worked hard to make vocals and instruments sound larger than life. Over the years, they’ve used all kinds of techniques to achieve this: equalization, compression, distortion, enhancers, delays, and reverbs are all familiar examples.

But one of the simplest and most effective ways to add power to a sound is by doubling or layering it—and in this article, we’ll walk you through a few easy and efficient methods you can try in your DAW.

This approach creates width and depth in your mixes, and by panning layers left and right (with a bit of spatial widening here and there), you can really make a track sound massive.

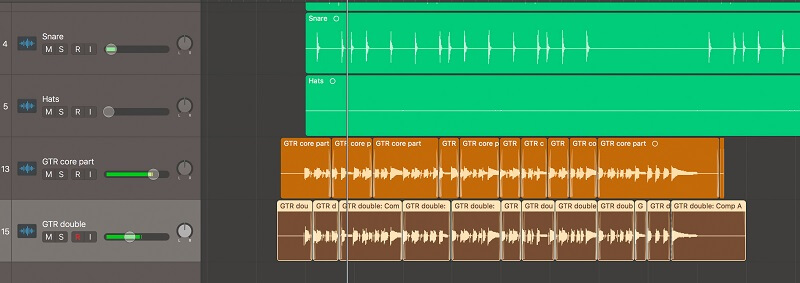

You’ll see this technique used again and again—especially in modern rock and metal mixes, where more guitar parts usually means a bigger sound. Quad-tracked and layered rhythm parts build on the classic stereo approach, and it seems like new ways to achieve even bigger, bolder sounds are always emerging.

However, engineers often overlook double-tracking when it comes to lead guitars, where there’s still a lot of sonic space to fill. That’s where we’re going to focus our attention today.

The Fundamentals of Doubling Tracks

Traditionally, the best way to achieve doubled vocals was through “double-tracking,” where the artist would simply record their lines twice. However, sometimes the singer isn’t available for extra recording sessions, or you might be the hired mixer who only receives vocal stems without any doubles. Other times, the singer may struggle to perfectly overlay the same vocal line twice.

The style of production might also call for a cleaner, more “perfect” double, rather than a natural-sounding one. These are all situations where creating artificially double-tracked vocals can be the right solution.

When you want precise vocal doubling, look no further than Waves Doubler. This plugin lets you create artificial vocal doubles by duplicating, panning, and adjusting the pitch of your original vocal track.

Waves Doubler goes even further by letting you add feedback, modulate pitch at different rates, and EQ your doubled vocals with both low-shelf and high-shelf filters. There’s also a convenient output gain fader, so you can easily control the plugin’s output level.

Should you still be recording doubles?

The key to double-tracked efficiency is keeping the two performances tightly synced—they should lock in together, or it quickly becomes obvious that they’re separate takes.

To achieve this, many engineers will record multiple times, working to get two performances as closely aligned as possible. After that, it’s a matter of stretching and aligning the audio even further until the timing is as perfect as they can make it.

Even when the performances are locked in, the harmonics won’t be identical. There are natural differences every time you play something, from how hard the string is plucked to slight changes in tuning and the magnetic pull of the pickups. All these tiny variations create the sweet harmonic saturation we love when we hear two nearly identical tracks played back at the same time—and they’re exactly what you want in a perfect doubled lead.

When do you have to double your Vocals?

Here are some situations when you might want to record a vocal dub:

- If you’re aiming for that classic hip hop vibe—especially if your beat sounds like something from over a decade ago—definitely consider recording vocal dubs.

- If you’re working on R&B, rock, country, or any genre that involves singing, you might also want to add vocal dubs. Just keep in mind that doubling vocals can sometimes take away from the intimacy of the lead vocal.

- For choruses—whether in rap or any singing style—your audio engineer can use vocal doubles to pan to the sides for a wider stereo sound. Usually, it’s a good idea to record extra vocal layers of the main vocal and pan them left and right. However, this isn’t necessary for every song.

What’s ADT (Artificial Double Tracking)

If you’ve ever tried to deliberately double-track a vocal, you know just how much harder it is than it sounds. Trying to match the timing and subtle nuances of a vocal can be very time-consuming and incredibly frustrating for both the singer and the production team.

That’s why Abbey Road’s chief engineer, technical director, and later studio supervisor, Ken Townsend, came up with a brilliant way to simulate double-tracking for The Beatles. By using a couple of tape machines, he created an effect that’s still tough to perfectly recreate today (although Waves now offers a nice simulation). He called this effect ADT, or Artificial Double Tracking.

These days, we have a lot of tools to help shape our sound and get close to that ADT effect, but nothing truly matches the original. Some people even say that Townsend’s invention is the closest artificial double tracking has ever come to sounding like the real thing.

The Beatles—and John Lennon in particular—loved the sound of double-tracked vocals but hated actually recording them. Plus, back in the days of four- and eight-track recorders, doubling vocals meant using up a track that could have been used for something else.

The solution Townsend came up with was ingenious, especially given how limited the equipment was in the 1960s compared to today. Still, it’s a pretty complex setup that you can only truly understand if you know how three-head tape machines work.

The right way to Double Track?

There are a couple of ways you can approach vocal doubling, and each method creates a slightly different result. Which one you choose depends on the kind of doubling effect you want to achieve.

The goal in every case is to closely match the original vocal recording—without making it an exact copy. You want the doubled track to sound a bit different from the original. This thickens the overall vocal part and makes it more interesting. If both vocal tracks are identical, you’ll just get a louder sound, not a fuller one.

Record again

Recording another vocal track underneath the original is both the simplest and most challenging way to double vocals. The process itself is straightforward: just record a new take of the same vocal line. The challenge comes from human error.

Some human error is actually what you want here. Remember, you don’t want an exact replica of the first vocal track. However, you also don’t want the double to be too far off in pitch, timing, or tone, or it will hurt the mix instead of helping it. That’s why it’s best to record the double right after the original. The closer together you track them, the more likely the doubled part will fit. Also, it’s important to pan the original and double in opposite directions. Doubling vocals, like doubling guitars, works best when you spread them out in the stereo field.

In some cases, you can stack both takes in the center to get a thicker and more complete sound. After recording, you’ll need to blend and glue them together so they feel like one unified part.

Automate the process

If manually recording a double isn’t giving you the results you want, there are other options. One popular method is called automatic double-tracking (ADT). This technique only requires one vocal track, but it creates an artificial doubling effect. Ken Townsend, the Beatles’ recording engineer, invented a way to mimic manual vocal doubling in 1966 using tape delay.

Basically, ADT is like using delay on any other instrument. Just as certain delays, like doubling echo, can thicken a guitar track, ADT takes the vocal input, plays it back with a delay, records this duplicate, and then combines both tracks. The duplicate will be slightly different in timing, decay, and placement, making the vocals sound fuller and richer.

Back in Townsend’s day, all of this was done with analog equipment. Today, ADT is digital, although some engineers still prefer the vintage sound of analog tape delay. In reality, the results are pretty much the same. Digital ADT can be done with plugins in most DAWs, or with special software like Reel ADT and KVR: ADT. Most of these plugins also offer stereo options to spread the doubled vocals across the left and right channels.

Conclusion

Doubling is often an extremely misused technique for tracking vocals and instruments. Many people don’t realize that it can actually ruin the mix or the element they’re trying to enhance.

Going forward, always remember to take the time to record a clean vocal. It should match the main track without being overly edited or perfectly lined up.

When mixing, don’t automatically pan your tracks left and right unless they’re backup vocals. Removing some high-end and sibilance, or processing the double with a different sound, is another effective approach. This ensures that your vocal doubles serve only to fill out and support the main vocal, rather than distracting from it.