How to EQ Acoustic Guitar

Introduction

In this article, we’ll show you how to EQ an acoustic guitar so it stands out in the mix. We’ll guide you through finding the best settings to help your acoustic sit nicely without clashing with other sounds.

These EQ techniques work well for both live-recorded guitars and VST guitars. Whether your acoustic is recorded through an amp or audio interface, make sure it sounds great at the source before you start mixing.

You can also use these methods on other string instruments, such as ukuleles, banjos, or ethnic guitars.

This tutorial will be helpful even if you’re using a guitar with inexpensive strings. Below, you’ll find a simple guide to getting the best settings when mixing an acoustic guitar.

Make Things Proper From The Start

Before you start recording and mixing, take a moment to think about how you want the final guitar track to sound, and plan your setup accordingly.

For example, if you want the guitar to sound bright and clear, use a large diaphragm condenser microphone and place it a bit farther from the guitar (about 5–10 inches away).

On the other hand, if you want a warm and intimate sound, use a dynamic microphone and position it closer to the guitar (about 2–5 inches away).

Because this step is so important, we want to highlight it right at the start of this article. Take the time to get it right.

Trim the excess frequencies

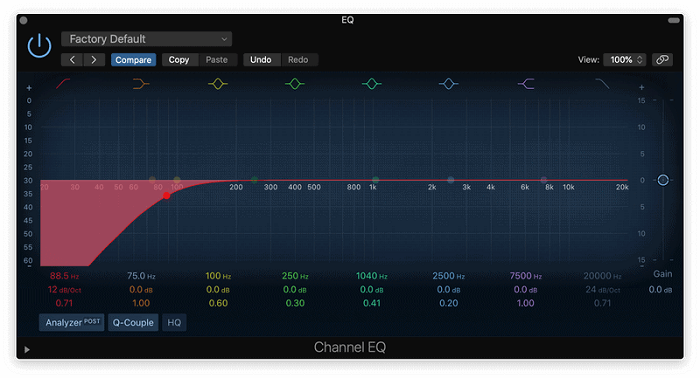

Mixing consoles have a channel-level control labeled “HPF,” which stands for high pass filter. The HPF allows only higher frequencies to pass through, cutting out the lower ones. Don’t overlook the high pass filter—it’s a great tool for balancing the frequency spectrum, trimming the low end, and cleaning up your acoustic guitars. This is exactly what you want to use when you’re starting out with acoustic guitar EQ.

On analog mixers, the HPF usually has a fixed frequency setting, often at 100 Hz, or sometimes a knob to adjust the range. If you see a button labeled “/100,” that’s the HPF, and it’s set to cut everything below 100 Hz.

Turn on the HPF so that all frequencies below its set point are removed. These low frequencies can muddy up your guitar sound. Other instruments on stage, like the bass and kick drum, are better suited for handling those deep tones.

If your HPF has an adjustable frequency, start around 100 Hz and raise it as needed. Sometimes, we’ve set them as high as 230 Hz because, for that particular guitar, a 230 Hz HPF gave us the sound we wanted.

Remember, there’s a big difference in control between analog and digital mixers. Use these tips according to how your mixer works and its specific limitations—no need to repeat what you already know about your own gear.

Controlling Low Frequencies

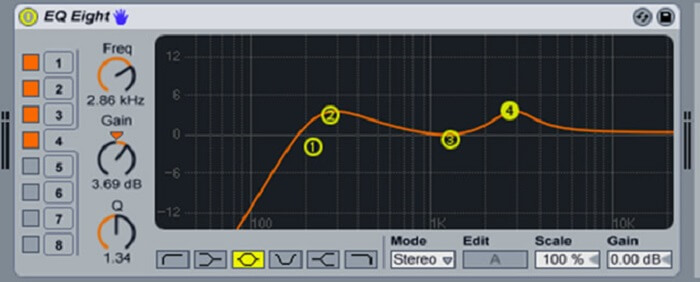

At this stage, focus your attention on the upper bass frequencies, typically ranging from around 80 Hz to 250 Hz. Usually, you’ll want to use a low-shelf EQ set somewhere around 250 Hz to 300 Hz, and experiment with gently reducing these frequencies as a whole.

Often, this simple approach will get your sound very close to where you want it to be.

However, you might notice that while you’ve made significant improvements, the low end now feels like it’s missing some “oomph,” especially with the 5th and 6th strings.

To address this, try adding a slight boost around 150 Hz. We recommend using a wide Q and boosting no more than 5 dB.

A broad Q keeps the transition between frequencies smooth and musical, rather than abrupt and obvious. This is especially important in the bass range, where a lot of energy is present.

Try moving your center frequency around with different amounts of boost to find the sweet spot. Once you find it, you can further adjust your Q as needed.

Character

Changing the EQ on your amp can really change its overall sound. Even if your amp doesn’t have a midrange knob, there are still ways to adjust the midrange balance.

Take the Fender Princeton, for example. The Princeton doesn’t have a midrange knob—its mids are set by the circuit. But if you lower the bass or treble, you’ll let more midrange frequencies come through.

The Vox AC15 works in a similar way. When you turn down the treble knob, you’ll hear more upper mids. If you reduce the bass, you’ll get more lower mids. Take the time to get to know your amp!

You should always adjust the EQ based on the guitar you’re using, the room you’re playing in, and any effects you have on. Don’t assume you can just fix your tone later.

Match It Into The Mix

Un-solo the acoustic guitar and listen to it with the rest of your mix. From this point on, avoid using the solo button. You simply need to break the habit of using the solo button—there’s no way around it. We know this might be tough, but do your best to unlearn this unhelpful method.

Pay attention to how the acoustic guitar interacts with other tracks in your mix. Be especially mindful of the low end—often, you’ll need to roll it off to make more space for the kick and bass.

You can usually cut out quite a lot, sometimes everything below 300 Hz.

Also, listen to how the acoustic guitar and vocals sit together. A gentle cut in the upper midrange often helps them fit better. This is the best way to make space for the guitar while letting it shine. If the acoustic guitar is the main focus of your song, make sure you give it the attention it deserves.

Again, all of this depends on the context. We wish there were a formula, but the key is to listen to the whole mix and let that guide your decisions. Resist the urge to solo!

Don’t forget to pan, too. If the acoustic guitar’s EQ is clashing with another track, try panning the two tracks to opposite sides first. This often creates separation without needing to use EQ.

Pay attention To The Bigger Image

A common mistake is to solo an instrument when you’re making changes to its sound. If you think about adjusting the position of your acoustic guitar, working in solo can actually hurt your mix.

When you listen to the acoustic guitar by itself, you might make choices about what to change without considering the full picture. The guitar might sound great on its own, but as soon as you un-solo it, you might wonder why it no longer fits in the mix.

This happens because every part of the mix affects how your acoustic guitar EQ sounds. The only way to make adjustments that actually improve the overall mix is to listen to the guitar in context with everything else.

Clear it up and make it good

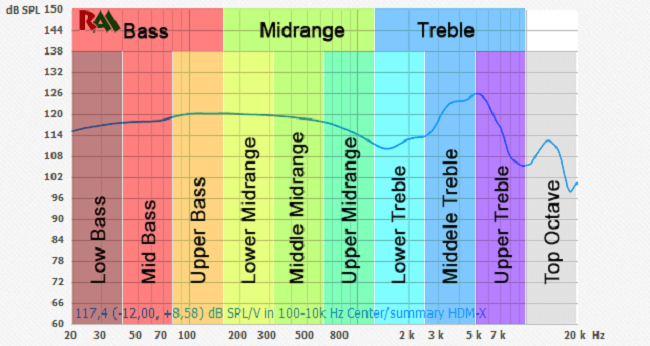

The following breaks down frequencies into EQ ranges. Digital consoles can work with completely different frequencies, but basic analog channel EQs with only 3 or 4 knobs won’t give you the same level of control.

Check out this article for tips on improving your mixes with an analog mixer (these tips work for digital mixing, too). Apply these suggestions as they fit your situation best.

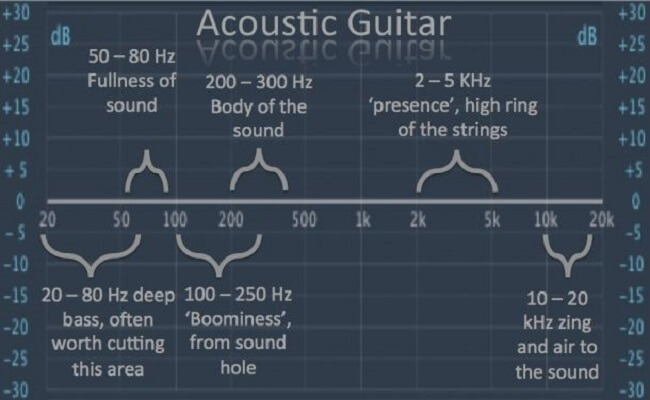

- 150–300 Hz range: Use this range to add fullness to the guitar’s tone. However, be careful—boosting too much here can make the sound muddy. Only increase these frequencies if it clearly improves the overall sound.

- 300–600 Hz range: Boost this range if your guitar sounds thin.

- 600–800 Hz range: This is your meaty midrange sound. Cutting this range can help create a cleaner tone and make the guitar stand out from other instruments.

- 1,000–3,500 Hz range: These frequencies can bring the guitar forward in the mix and improve note definition. Boost in this area for fingerpicking and lead guitar (not rhythm guitar).

- 3,500–12,000 Hz range: This is where the sparkle lives. These frequencies add brilliance and can help the guitar pop in the mix. You can break this range down further: 3.5–5 kHz, 5–8 kHz, and 8–12 kHz. Start by adding a bit at 3.5–5 kHz for acoustic guitar sparkle. If you want more, try boosting a little in the next range up.

Use Busses To Make Mixing Simpler

If you’ve recorded acoustic guitar using several microphones, or if your session has multiple guitar parts, it can be tough to keep everything organized.

When you’re trying to manage all those tracks and their levels, bussing is your best friend. Send all the microphones used for one acoustic guitar to a mix bus. You can even send each separate guitar part to its own bus, with all the guitar parts feeding into a main guitar bus.

At first, this might seem a bit redundant or unnecessary. However, as you keep mixing and need to make quick changes, you’ll be glad you took the time to set things up early on.

How does EQ have an effect on a guitar’s tone?

As we discussed earlier, any sound—whether it’s isolated or coming from multiple sources like a band—creates a unique sonic footprint. Our ears pick up this footprint as a single experience. The way different sound sources are combined determines how the overall mix sounds to us.

This is what makes sound engineering such an art form. Engineers need to ensure that all the different instruments have their own space within the EQ spectrum so each one can be heard clearly. If this isn’t done well, instruments can overpower each other or blend into an indistinct mush.

This challenge is especially true for guitars, which are very mid-range focused. They often compete with other instruments in the same frequency range, like the saxophone, vocals, drum toms, and even other guitars.

The mid-frequency range is typically filled with these instruments, so you don’t want your guitar to get lost or become too dominant in the mix. You have to find that perfect little pocket of space, and you can do this by using an EQ pedal to shape your tone and fit it right where it needs to be.

Three EQing Errors

“We’ll Just Fix It In The Mix”

You’ll never get a great-sounding mix if you rush through the recording stage. Take the time to get your acoustic guitar sounding fantastic right from the start. You’ll end up needing less EQ, and your final mix will sound much better.

Adding Too Much Top End

Boosting high frequencies can be tempting. When done right, it makes acoustic guitars sound clear and vibrant. But if you go too far, your track will end up sounding harsh and thin.

A quick tip—be extra careful when boosting the upper midrange. Our ears are very sensitive in this area, and it can easily become harsh or aggressive.

Boosting Too Much Bottom End

We rarely boost the low frequencies on acoustic guitars (unless the original track sounds really thin). In most mixes, you’ll want the kick and bass to control this part of the frequency spectrum.

That said, always trust your ears. If it sounds good, it is good! Just be cautious.

Here are some EQ tips for getting a great acoustic guitar sound:

- Cut the lows – Remove unnecessary bass frequencies to help your guitar sit better in the mix, especially when playing with a band. These low frequencies can clash with the drums and bass.

- Remove nasal frequencies – These are usually in the upper midrange and can often be reduced or removed completely for a smoother sound.

- Clean up the muddiness – Lower mids can make your guitar sound muddy, so reduce them to get a clearer tone.

- Add clarity – Don’t be afraid to add high frequencies to make your acoustic guitar sparkle and shine.

- Shape the overall tone – Most importantly, use your ears. If you need to adjust a frequency—even if it goes against the “rules”—do it!

Conclusion

For such a simple instrument, you’ve probably realized by now that there’s actually a lot to consider when mixing the acoustic guitar. Don’t be intimidated, though—after trying out these techniques on a few songs, it’ll soon become second nature.

The biggest takeaway from this article should be to always think about the role the acoustic guitar plays in the mix. This will guide how you use EQ, compression, reverb, and delay.

We always love a song that features acoustic guitars. Processing this instrument and making it shine in a mix is something we really enjoy. Aside from EQ, there are other steps you can follow to make your acoustic guitar sound even better, but here we’re focusing just on this process.

Checking the phase of microphones and properly balancing them with buses is also important to keep in mind as you mix.

Finally, using automation will help your guitar’s sound evolve as the track builds. Follow these tips and you’ll be able to take the sound of your acoustic guitar to the next level in no time.